Overview

How do you close a deal when the buyer and seller can’t agree on what the business is worth today? In today’s market, where forward projections are harder to underwrite and valuation gaps are widening, Earn Outs have become a commonly used structure to reconcile differences and move transactions forward.

Rather than stretch on price or exit the process, buyers can defer a portion of the purchase price, tying it to future performance and sharing risk with the seller. These payments are typically linked to achievement of future revenue, EBITDA, or other specific milestones, and are especially common in founder-led, growth-stage, or milestone-dependent businesses.

While conceptually simple, Earn Outs introduce real complexity - impacting cash flows, return timing, and deal dynamics post-close. They require thoughtful structuring and careful modeling to ensure their impact is clearly understood and accurately reflected.

This writeup breaks down the most common Earn Out structures, how to model them in an LBO context, and key considerations around return analysis, payout mechanics, and risk.

Why It Matters

Earn Outs are a practical lever to get deals over the line, especially in situations where forecasted performance is central to valuation. For private equity sponsors, they can:

Reduce upfront equity investment

Preserve upside while mitigating downside

Improve alignment with management teams

Strengthen bids without raising headline valuations

They’re frequently used in founder-led businesses, growth-stage companies, and sectors like software, healthcare, and regulated industries, particularly when performance hinges on the achievement of specific commercial milestones like FDA approval, payer contracts, or customer wins.

Common Earn Out Structures

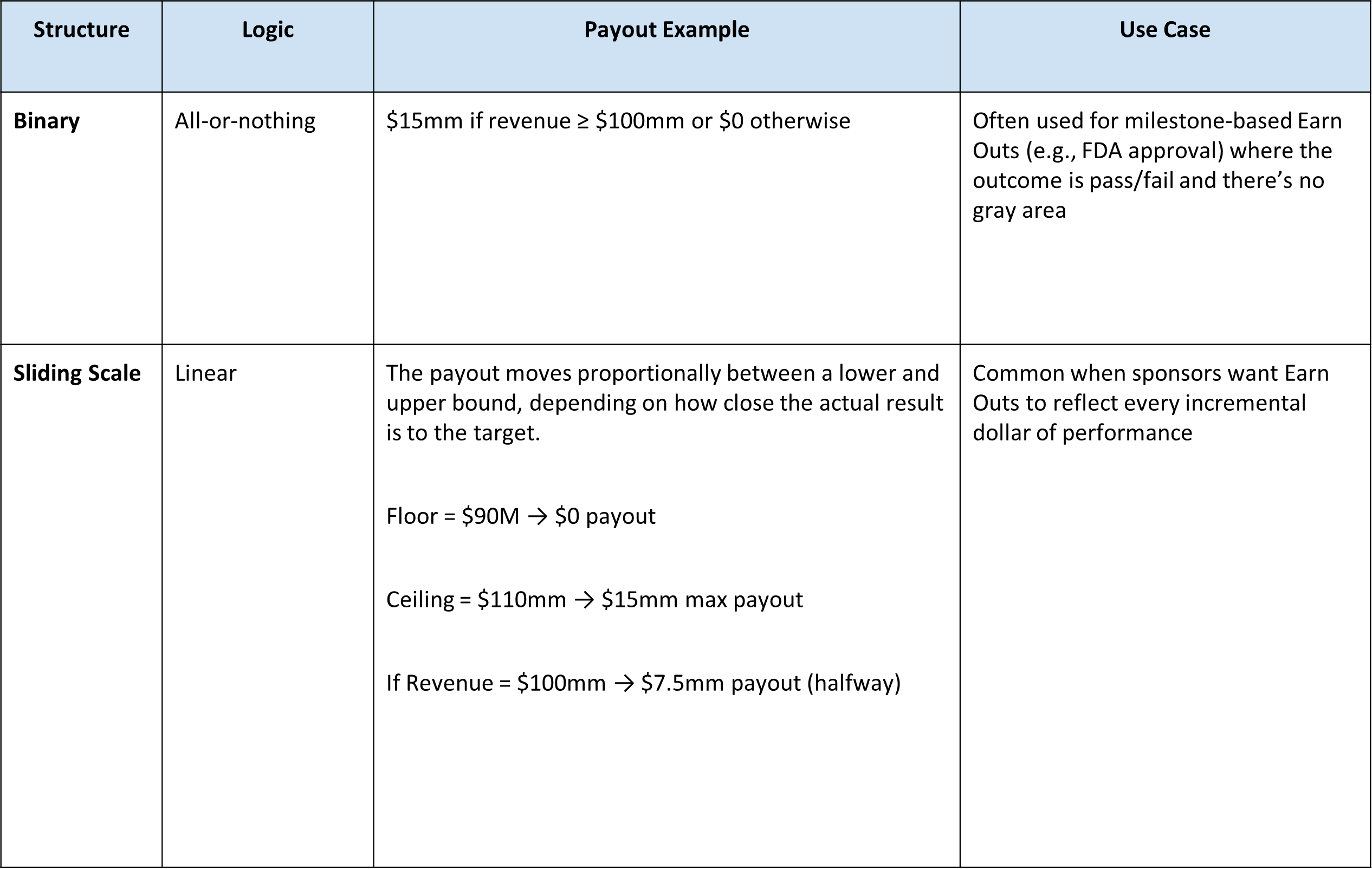

Earn Outs can be binary or sliding scale, depending on how close the performance comes to the agreed targets. There’s no one-size-fits-all approach, but most private equity earn-outs fall into a few general buckets:

Revenue-based: Payment is triggered when the business hits a defined revenue milestone (e.g., $150mm in FY27).

EBITDA-based: The most common structure is tied to achieving a target EBITDA level.

Margin-based: Used when margin sustainability is in question or when cost structures are volatile.

Milestone-based: Non-financial triggers like product launches, regulatory approvals, or enterprise customer wins.

Earn Outs typically range from 5–25% of enterprise value in mid-large cap deals, though the structure and size can flex significantly based on the nature of the business and the perceived risk around projections.

Modeling Earn Outs in an LBO

Modeling Earn Outs requires a few additional steps, especially because they impact not just total consideration, but also cash outflows, equity sizing, and return timing. They don’t flow through every model in the same way, and it’s easy to misrepresent their impact if not handled carefully.

Step 1: Define the Structure

Before anything hits your model, make sure you get clarity on the Earn Out terms. At a minimum, you need to know:

Performance Metric: What’s the basis for payout? Revenue? EBITDA? Gross Margin?

Target Amount: What level of performance triggers the Earn Out

Timeframe: What year(s) post-close are evaluated (e.g., FY28 / Year 3)?

Payout Mechanism: Is it binary (hit or miss) or on a sliding scale?

Maximum Earn Out Value: What’s the ceiling? Typically expressed in dollar terms or as a % of TEV.

Payment Timing: When is the Earn Out paid? Year-end? Over multiple years?

Tax Treatment: Is the Earn Out deductible to the buyer? This can materially affect cash tax modeling and net proceeds.

Step 2: Build Core Projections Without the Earn Out

Model your baseline financials without the Earn Out first. This gives you a clean reference case and ensures that you’re not back-solving your base case around a payout structure and gives you a clear benchmark to test performance scenarios against.

Step 3: Add Earn Out Logic

This is the heart of the Earn Out implementation. Build a structured calculation block that:

Evaluates the performance target:

Is the metric met or not?

If on a sliding scale, what proportion of the target was achieved?

Calculates the payout:

Full payout? Pro-rata? Tiered?

Cap the payout at the agreed maximum

Applies timing logic:

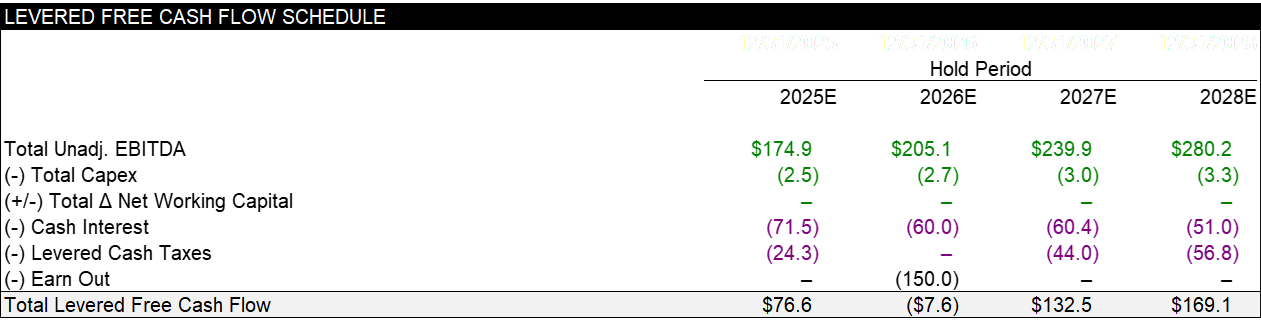

Insert the Earn Out as a cash outflow in the appropriate year(s)

Reflect the tax shield, if applicable

Earn Outs can meaningfully impact IRR by shifting return timing, especially when payouts occur closer to exit or refinancing windows. Sponsors often build in liquidity buffers to avoid cash surprises in these periods.

How Mosaic Handles Earn Outs

Earn Outs can be highly variable across deals, making the modeling exercise both time-consuming and error-prone in Excel. Mosaic streamlines this process by allowing deal teams to structure and flex earn-out assumptions directly within the Special Situations panel - no manual overrides or custom logic required.

Users can:

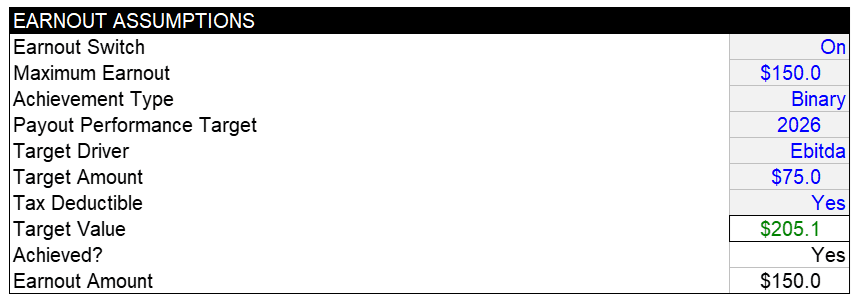

Set the Maximum Earn Out (e.g., $20mm cap)

Choose the Achievement Type – Binary (hit/miss) or Sliding Scale

Define the Performance Year (e.g., 2028 – Year 3)

Select the Target Driver – Revenue or EBITDA

Set the Target Amount (e.g., $100mm)

Specify the Tax Treatment (deductible or non-deductible)

Earn Outs offer flexibility, but they also introduce complexity. Common pitfalls to avoid:

Management turnover: If sellers or key execs leave, the Earn Out might become irrelevant or harder to achieve.

Liquidity surprises: Earn Outs might feel “off-balance sheet,” but they still require planning - especially if they’re large or come due near a refinancing or dividend recap.

Exit complications: A live Earn Out can complicate a future sale, as the next buyer may demand indemnities, discounts, or escrow until it’s resolved. In some cases, sponsors may proactively settle or renegotiate Earn Outs before exit to clean up the capital structure and reduce friction with potential acquirers

Earn Outs may also interact with other elements of consideration like seller notes or equity rollovers. For example, a seller who rolls equity and also has a large Earn Out may be economically over-indexed on post-close performance, requiring careful incentive planning.

Earn Outs don’t fit every deal. They’re typically avoided in:

Heavy turnaround situations, where performance is highly dependent on sponsor-driven restructuring

Carveouts, where standalone historicals are unclear and clean baseline metrics are hard to define

Deals where post-close strategy involves significant integration or operational changes, making it hard to isolate what performance is “organic”

Summary

In summary, Earn Outs are a flexible tool to reconcile differences in valuation, especially when forward projections are aggressive, uncertain, or tied to specific milestones. While straightforward in principle, their real impact on deal economics depends heavily on how they’re structured and modeled.

The variability in payout mechanics - whether binary, tiered, or prorated - combined with considerations like timing, tax treatment, and interaction with other deal elements, makes accurate modeling critical. Yet in practice, Earn Outs are often modeled inconsistently or incompletely, leading to misaligned IRRs, equity miscalculations, or underappreciated risk around liquidity timing and exit complications.

Despite being contingent, Earn Outs represent real obligations that can meaningfully shape outcomes. Whether they ultimately pay out or not, they deserve the same level of rigor as any other component of the capital structure.